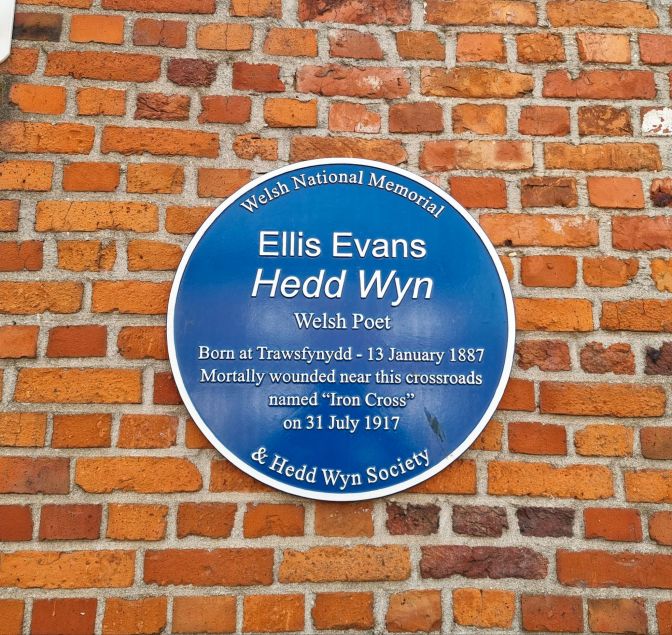

The intersection of Boezingestraat and Groenestraat slumbers in the silent heart of Flanders Fields. Red-bricked buildings sit on three of its corners, a noble farm field on the other. Besides the well-manicured rows of ploughed earth, the intersection shows little signs of life or purpose except for the presence of curtains or half-drawn blinds. One of the buildings looks like it once was a pub and may still be used today as a festival hall for rent. A sign forms the curious word Croeso over one of the windows. It is hard to imagine anything other than ghosts and dust occupying these forlorn grounds. Across the street, breaking up the stillness, a Welsh flag flaps in the wind guarding over a handful of plaques. They seem to whisper Why are we here at these lonely crossroads? A small round plaque tells of a Welsh bard who fell in battle here, when this hushed, humble land erupted into a nightmarish hell on the morning of July 31, 1917.

In the quiet eastern frontier of Snowdonia lies a mountain of “brooding solitude”1, Arenig Fawr. At 854m, it does not rank amongst the highest of mountains in North Wales, but it is known for its rugged beauty, so much so that in 1911 and 1912, two Welsh painters, James Dickson Innes and Augustus John devoted their time painting landscapes of it2. About 11km to the west of the peak sits a small farmhouse where at the time Innes and John were painting, Ellis Evans was honing his skills as a poet.

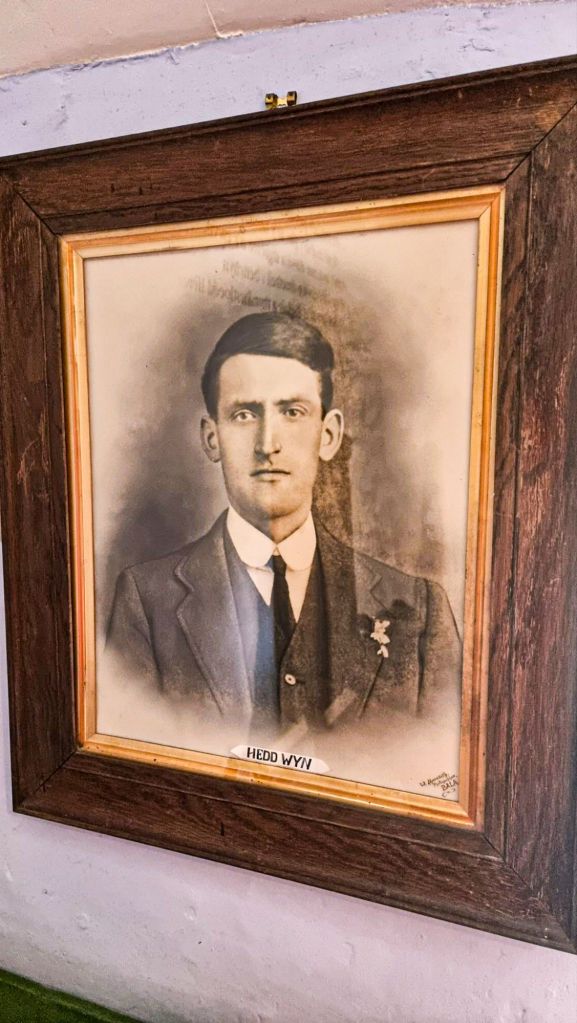

Wales has a long tradition of bardic competitions called Eisteddfod going as far back as possibly 1176. There are local smaller Eisteddfod as well as the National Eisteddfod which is held the first week of August every year. The most prestigious award is a chair awarded for the best awdl, a long poem with a strict meter. Ellis Evans, who was given the bardic name of Hedd Wyn (which means Blessed Peace), won his first local Eisteddfod at the age of 20 in 1907. After several more chairs on a local level, in 1916, he finally broke through at the National Eisteddfod with a second place finish.

Then came 1917.

Hike Details

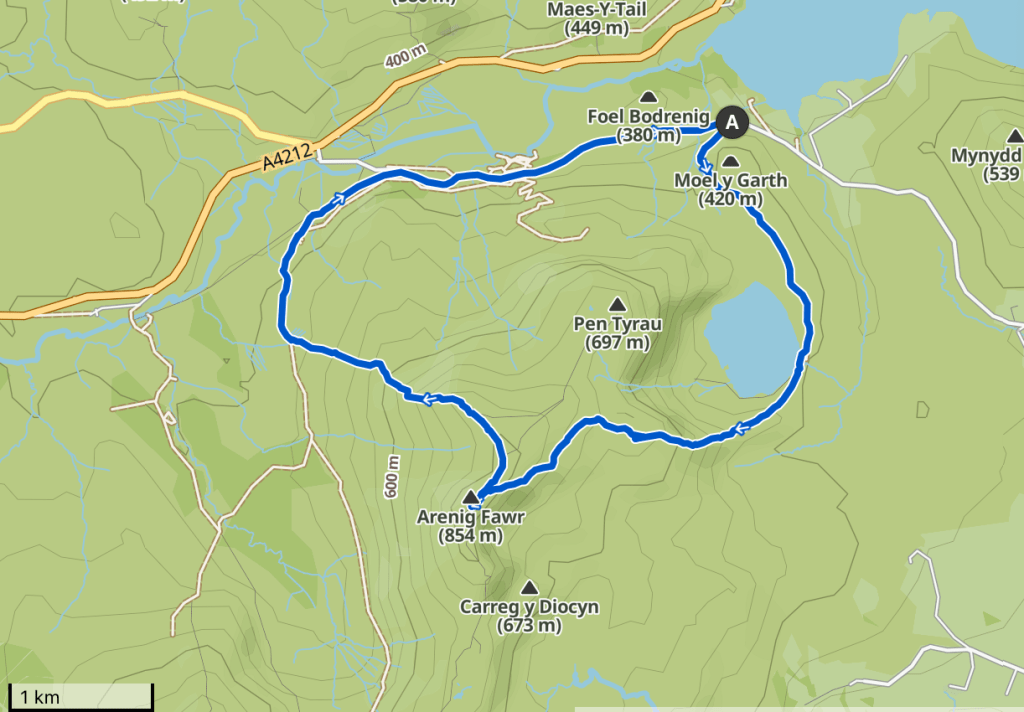

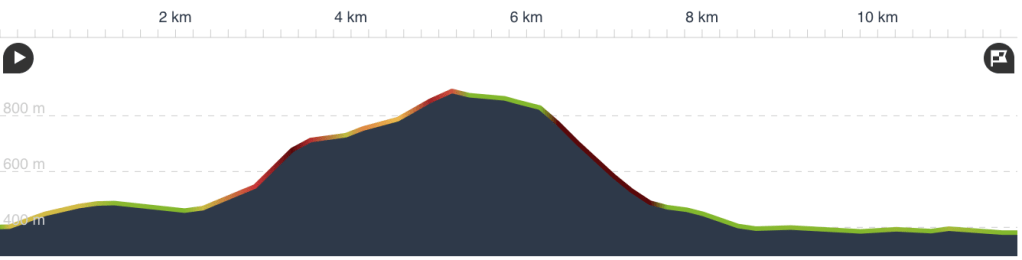

Arenig Fawr would be my final hike during my August 2025 visit to North Wales. After the hike, it is a short drive to Yr Ysgwrn, the homestead of Hedd Wyn which is now a museum maintained almost exactly as it was when Hedd Wyn lived there. The final stop would in be the nearby village of Trawsfynydd for the celebratory beer. It is quite an easy hike with no tricky parts, but it continued the theme of the week of having to traverse unavoidable soggy marshes which inevitably leave you with soaking wet shoes.

| Starting/Ending Point | A small parking area along the Arenig Fell Race road |

| Distance | 11.6 km |

| My Moving Time | 2h 42m |

It’s Not Just a Beer, It’s a Journey

“Of all the hills which I saw in Wales, none made a greater impression upon me.”

Wild Wales: The People, Language, & Scenery by George Borrow (1906)

Despite the notoriety brought by the paintings of Innes and John, Arenig Fawr is referred to as “little traversed”3 and “not being climbed by the tourists”4. As a point of fact, it was the only hike of the week where I did not see a single soul from the moment I left my car until the moment I returned to it.

The initial ascent is up this clean track. The mountain visible in the distance is only part of a ridge which surrounds a small lake Llyn Arenig Fawr.

When the peak comes into view (right-most peak in the next photo), you can see that the peak is part of a long ridge. There is a longer version of this hike that would follow this ridge, descend, and wind around to another peak called Moel Llyfnant (751m) which would have added another 5km, but I wanted to keep the hike shorter.

At the summit is a memorial to the American crew of a B-17 Flying Fortress bomber which crashed here on August 4, 1943. Some of the crash wreckage is still found there.

The view from the summit is commanding. I captured a shot of a glider flying above the Arenig valley. If you follow a line in a northwest direction from the glider at just below cloud level, you will see the profile of Cnicht from its non-Matterhorn-looking direction. In the very center is the mammoth mass of Yr Wyddfa covered by clouds as it normally is.

As you descend into the Arenig valley, it is easy to understand what captivated both Innes and John back in 1911 and 1912.

As you reach the valley floor, you come to the messy part of the hike.

With a much better view of Moel Llyfnant, I was feeling the tug of regret that I didn’t include it.

The last segment of the hike is mostly uninteresting and just follows the same road that I drove in on. But it afforded a view of where the Arenig train station and tracks used to be.

Yr Ysgwrn

Towards the end of 1916, Hedd Wyn was coming off his second place finish in the National Eisteddfod when he got word that his family had to provide one son to go fight for Great Britain in Belgium during World War I. Farming families often were exempt from conscription into the military. However, the war was about to enter its fourth year and more soldiers were needed. Hedd Wyn was a pacifist and up to that point had chosen not to enlist. But to prevent his younger brother from fulfilling the family obligation in 1916, he decided to take his place. He was given leave to return home in March 1917 for a few weeks to assist with the farm work. During this time, Hedd Wyn managed to finish the poem he would submit to the National Eisteddfod, Yr Arwr meaning The Hero. He overstayed his leave by one week and was briefly arrested for desertion before being shipped off to Belgium. In the chaos, he managed to leave the poem behind. On the way to Belgium, he was able to compose the 25-page poem completely from memory. While stationed in France, he was allowed to finally mail his poem. Hedd Wyn used the pseudonym Fleur de Lys for his submittal.

That year, the National Eisfeddtod was held during the first week of September near Liverpool, England and attended by British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George. When the winning poem was announced, the author Fleur de Lys was asked to stand. The question was asked three times to silence before the shocked room was informed that the author, Hedd Wyn, had been killed in action at the Battle of Pilckem Ridge in Flanders Fields just a few weeks earlier. His chair was draped with a black cloth and ever since has been referred to as the black chair.

A transcription of the winning poem Yr Arwr can be found in its original Welsh with an English translation here.5

Trawsfynydd

In the nearby village of Trawsfynydd, there is a statue in honor of Hedd Wyn. Here also is the Cross Foxes Inn where I enjoyed a beer from the Purple Moose brewery in Porthmadog. Afterwards, I took a walk around the small village with it’s quaint St. Madryn Parish Church and churchyard looking towards Llyn Trawsfynydd lake.

Final Remarks

During a charge which began at 3:50am on Pilckem Ridge near Ypres, Belgium, Hedd Wyn, a 30-year old farmer, poet, and pacifist was hit in the stomach by the nosecap part of an exploded shell. By 11am he was lying dead in the first-aid tent. He was one of almost 32,000 British casualties in the three-day battle.

In 1992, a biopic6 was made about Hedd Wyn which was the first Welsh movie ever nominated for an Academy Award. Watching the film while preparing this blog post felt like the culmination of my bike ride in Ypres in March 2025. On that bike ride, I passed several war memorials. It is easy to take them for granted; to glance over the name and move on. But noticing the Welsh connection, which lately appeals to me, I decided to seek out Hedd Wyn’s heritage in Wales. Arenig Fawr would probably have been far lower on my bucket list of Snowdonia mountains if it weren’t for the fact that it was situated near his home. As I toured his former home, the guide made a remark that I had come farther to visit the museum than anyone she had ever met. Normally, visitors are coming only from Wales and sometimes England. It is a regular pilgrimage for Welsh school groups. I did feel in some way like an outsider; like I had stepped into a private world where I didn’t belong. I have no interest in poetry, but I do understand the joy of composing words. Yet I didn’t comprehend at the time the importance of poetry to the national persona. I wondered to myself who is this guy whose name I saw on the plaque and whose living room I find myself standing in? Watching the movie and reading about the history of the Eisfeddtod finally made it all click. Hedd Wyn represents the Welsh ideal in so many ways. His rural background, his non-conformist attitude towards England, his passion to continue the long tradition of Welsh poetry. While I was there, the tour guide was sharing her own experience participating in a local Eisfeddtod. Meanwhile, I didn’t realize that in the city of Wrexham, the National Eisfeddtod of 2025 was actually ongoing. In 2026, it will be held in the village of Llantwd. It is a bit out of the way from my usual stay in North Wales, but who knows. The death of Hedd Wyn was one of a countless number of senseless deaths caused by war, but the legacy of it has inexplicably intertwined with my life and travel experiences in a way which to me is quite poetic. Wales, in general, has always made me feel welcome. And in fact, that is exactly what the word Croeso means.

- Rambles in North Wales by Roger A. Redfern (1968) ↩︎

- BBC Documentary clip ↩︎

- Odd Corners in North Wales by William T. Palmer (1937) ↩︎

- In Praise of North Wales by A.G.Bradley (1925) ↩︎

- https://www.liverpool-welsh.co.uk/images/HeddWyn.pdf ↩︎

- Link to the film on Youtube ↩︎

The village name, Croesor, in your previous post from Wales caught my attention. And now croesco, meaning welcome? I couldn’t not pipe up, if only to say, “Cool.”

I’d heard the story of Hedd Wynn before, somehow made more poignant in your telling. A different battle, on May 3, 1915, called the Second Battle of Ypres, inspired the poem, “In Flanders Fields,” by John McCrae.

Thank you for hiking up the spirit of Hedd Wynn. Let us know if you make the 2026 National Eisfeddtod.

LikeLiked by 1 person