“Between the completion of Oliver (Twist) and its publication, Dickens went to see something of North Wales”

The Life of Charles Dickens, Vol. I-III, Complete by John Forster (1875)

In the fall of 1838, Dickens took a “bachelor holiday”1 with his illustrator Hablot K. Browne (known as Phiz). According to his diary, he spent a grand total of two nights in North Wales, one in Llangollen, which is just across the border from England, and the other in Bangor, which is on the other side of North Wales along the Menai Straits, before returning to England. Unfortunately, there aren’t many details in his diary about this trip, but I will save this exploration for next year as I have the idea to follow in his footsteps. However, one detail he gives is the name of the hotel where he stayed in Llangollen; a hotel which still exists. This, of course, is a gold nugget for the subgenre of travel writing which you could refer to as Dickensian Inns & Taverns. Any establishment known to welcome Dickens as a guest is a pilgrimage for those who still care for that sort of thing (like me), and any establishment with those credentials would be wise to advertise it. But as I would find out, like lawyers, just because you hang a plaque on the wall doesn’t make it true.

In 1838, Dickens had only just achieved some fame with his first major publication, Pickwick Papers. But the part of Dickens’ connection to North Wales that I wanted to explore fast forwards to the year 1859. By 1859, Dickens was a world famous author with works such as Nicholas Nickleby (1839), A Christmas Carol (1843), and David Copperfield (1850) already released well in the past. He was in the midst of publishing A Tale of Two Cities as a weekly serial for his publication All the Year Round when in December 1859, he left for the Isle of Anglesey in North Wales.

Dickens arrived to a small Anglesey village called Moelfre to report on the aftermath of the events which occurred on October 25-26 when the region suffered a hurricane-level storm.

“Yet only two short months had gone, since a man, living on

The Uncommercial Traveller by Charles Dickens

the nearest hill-top overlooking the sea, being blown out of bed

at about daybreak by the wind that had begun to strip his roof

off, and getting upon a ladder with his nearest neighbour to

construct some temporary device for keeping his house over his

head, saw from the ladder’s elevation as he looked down by

chance towards the shore, some dark troubled object close in with

the land. And he and the other, descending to the beach,

and finding the sea mercilessly beating over a great broken ship”

This “broken ship” was The Royal Charter, a ship trying to reach Liverpool from Australia carrying around 500 men, women, and children. Many were gold miners and their families returning home to England. The exact count is not known due to the ship’s passenger logs being lost. Only 39 survived the wreck. Dickens spent much of his time visiting with the local Reverend Stephen Roose Hughes who took charge to recover many of the bodies and bury them in his churchyard. Dickens’ article would recite several heart-wrenching letters from surviving family members hoping to find their lost relatives.

The shipwreck occurred off the coast of the village of Moelfre, which is a little more than an hour drive from where I was staying in Beddgelert, so to take a break from my Snowdonia hikes during the first week of August 2025, I decided to take a drive and follow in Dickens’ footsteps.

Moelfre

“Moelfre has some of old-time Wales in its keeping, and long may it retain its simplicity.”

Odd Corners of North Wales by William T. Palmer (1937)

Moelfre is a sleepy sea-side village with one pub and everything huddled around a small beach. The walk along the coastal path is nice and leads past the memorial to the Royal Charter and a museum based on the local coastguard station. The wreck happened on the north side only 50 meters from the shore.

The Kinmel Arms

This is a great place to grab a picnic table outside and enjoy a fish & chips with a beer while watching the locals. Being the only pub in town, one would think that Dickens might have visited whatever rendition of this pub existed back in 1859, but I have found no reference to it. In fact, he doesn’t even mention the name Moelfre in his article.

A place Dickens does mention in the article is the church just a few kilometers away where Reverend Hughes buried the recovered bodies.

St. Gallgo’s Church

The walk up the lane to the church was timeless. Very little indicated any distinction between 1859 and 2025. Headstones tilted at all angles and the grass was mostly overgrown with paths groomed towards the more commonly visited grave sites and memorials, including that of the Reverend Hughes, which otherwise would have been difficult to find. If there was ever such a thing as a Dickensian churchyard, this is it. In fact, if you consider that the next book Dickens would write after this visit was Great Expectations, it would be hard to argue that this churchyard didn’t at least come to his mind a little when composing the opening scene of the book. Of course, it is widely accepted (and I agree) that the main inspiration was St. James Church in Cooling. Without further ado, I will let Dickens introduce the setting.

““He had the church keys in his hand, and opened the churchyard

The Uncommercial Traveller by Charles Dickens

gate, and opened the church door; and we went in. It is a little church of great antiquity; there is reason to believe that some church has occupied the spot, these thousand years or more.”

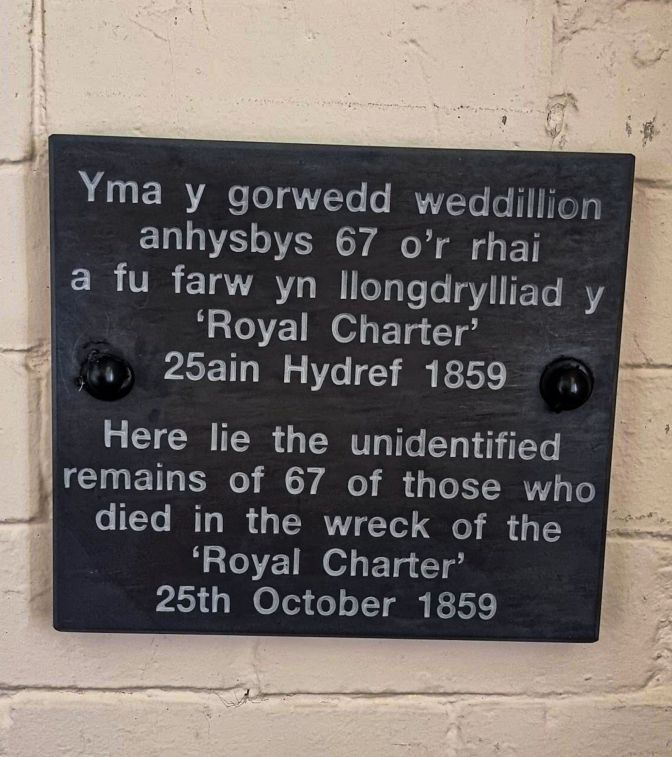

“From the church, we passed out into the churchyard. Here, there lay, at that time, one hundred and forty-five bodies, that had come ashore from the wreck. He had buried them, when not identified, in graves containing four each. He had numbered each body in a register describing it, and had placed a corresponding number on each coffin, and over each grave. Identified bodies he had buried singly, in private graves, in another part of the church-yard. ”

The Uncommercial Traveller by Charles Dickens

St. Michael Church (Penhros Lligwy)

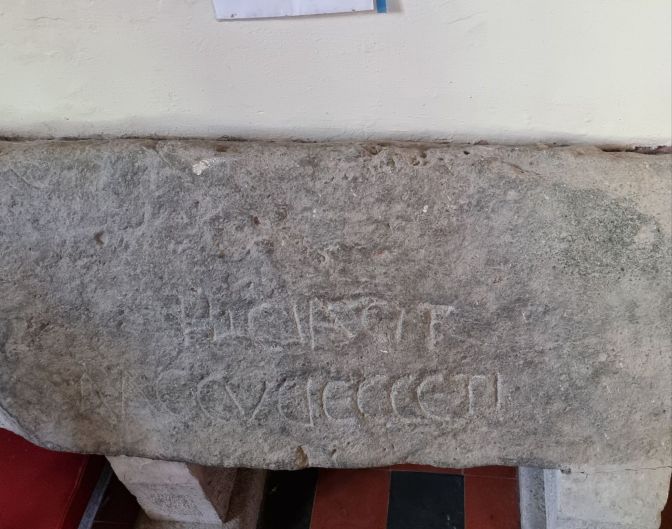

An even smaller and more remote church lies just a 3-minute drive west. Here, Reverend Hugh Robert Hughes, brother of Rev. Stephen Roose Hughes buried 34 of the bodies2. In parts of the churchyard, the grass is even wilder than St. Gallgo’s. Several of the headstones especially around the church have been swallowed up by tall grass. I spent quite a bit of time browsing those I could see, but I couldn’t find any that mentioned the Royal Charter. The most interesting feature is a stone found in the churchyard dating from the 6th century with a carved inscription on it HIC IACIT MACCVDECCETI meaning of Maccudecceti, here he lies. The name is believed to derive from Decens, the name of a God of the Decanti tribe which lived in this area.

It is not clear from The Uncommercial Traveller exactly how long Dickens stayed in the area. But it can be assumed that he spent at least one night here before returning home to London. None of my books gave any clues. So I turned to the keeper of all truths, the internet, for help, and I turned up two fascinating candidates. Fascinating in that both of them took me down a rabbit-hole of the sometimes shady world of Dickensian Inns & Taverns.

Panton Arms Hotel

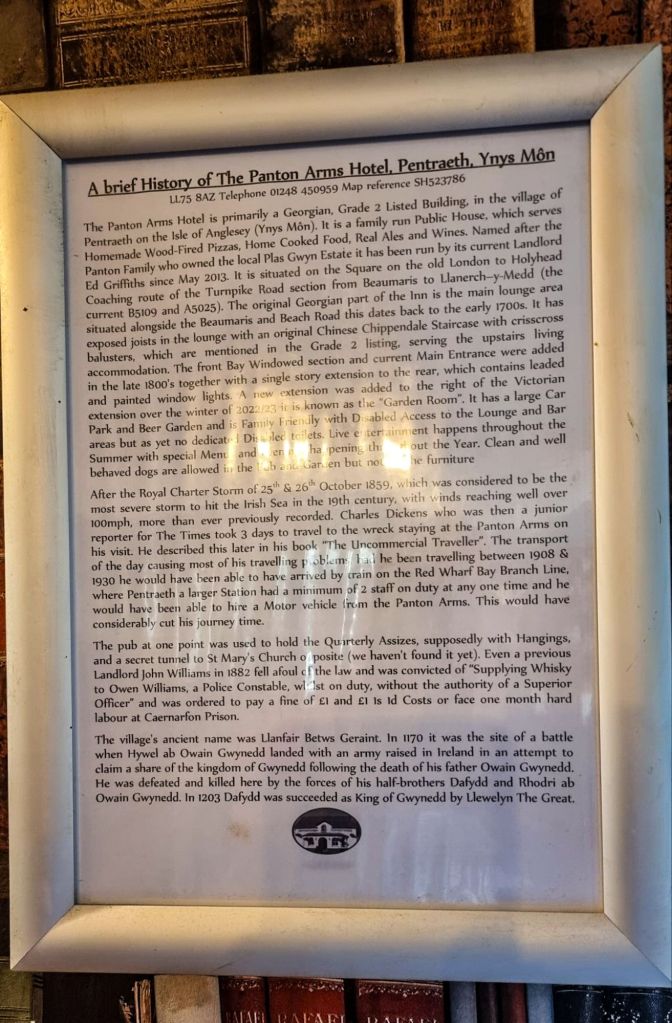

Just 10km from Moelfre is an old pub which very much looks the part. This has all of the characteristics you’d want in a Dickensian Inn, and to boot, the beer selection was tops of any place I visited during my week in Wales. I sipped a beer from the Purple Moose brewery from Porthmadog while getting a persnickerty old dog to warm up to me. Meanwhile I was pondering the history of the pub that was hanging proudly on the wall.

The part about Dickens goes like this:

“Charles Dickens, who was then a junior reporter for The Times took 3 days to travel to the wreck staying at the Panton Arms on his visit. He described this later in his book “The Uncommercial Traveller”.”

I found the same claim on the pub’s Wikipedia page with a reference to an article that was published on North Wales Live website originally in 2003. I will quote the article, if I may:

“CHARLES Dickens was a lowly newspaper reporter in 1859 when he was despatched at speed to cover the sinking of the Royal Charter, a steamer carrying 322,000 British Pounds in gold off the Moelfre coast. In direct contrast to today’s 24-hour news, Dickens arrived at the scene of the wreck three days after it sank. The delay was due to 19th century travel and a pub in Pentraeth called The Panton Arms. Weary from travelling, Dickens stopped at the Panton Arms for the night and some refreshment. And if the Panton had the same values then as it does now Dickens would have had a good night while still managing to keep a very modest expense account.“

As I sat there sipping my beer, I shook my head and thought Oh dear. In 1859, Dickens was certainly no “junior reporter” or “lowly newspaper reporter”. He was a world-famous author. He absolutely did not work for the (London) Times. This claim may derive from another article that inspired the next pub I visited. I will come back to that. Dickens was running his own weekly publication All the Year Round and was there of his own will and desire to report the good works of the Reverend. The Uncommercial Traveller mentions nothing about Dickens taking three days to reach there nor stopping and being waylayed by the discount prices of Panton Arms. He does allude to complications in his travel, but they started “that very morning” when he had “traversed two hundred miles”. Finally, Dickens did not reach the scene three days after The Royal Charter sank. He arrived two months later. Not only is someone duping someone else, but the village’s (Pentraeth) own Wikipedia page further perpetuates these falsehoods.

Nevertheless, the pub is worth the visit regardless of whether Dickens ever stayed there or not. That I cannot prove or disprove. The pub has certainly been around long enough to have existed when Dickens passed this way.

Ye Olde Bull’s Head Inn

The city of Beaumaris sits along the Menai Straits on the Isle of Anglesey about 18km from Moelfre. It is a historical town with a castle built by Edward I (a.k.a. Longshanks and Hammer of the Scots) during his campaign against Wales in 1282.

It is here at The Bull’s Head Inn where it is claimed that not only did Dickens stay, but he gave the pub a negative review in The Uncommercial Traveller. In 2012, this pub invited Dickens’ great great grandson Gerald Charles Dickens to give a reading, and an article was published about it in the North Wales Chronicle. The pub looks the part even more than the last one.

Let’s see what the article has to say:

“The legendary writer stayed at Ye Olde Bulls Head in Beaumaris while he covered the Royal Charter sinking in 1859 for the Illustrated London News, and later wrote a scathing attack on the inn’s food in one of his books.”

Is it The (London) Times or the Illustrated London News? The answer is neither. The article goes on to quote the modern Mr. Dickens as saying “It’s amazing to think I will be in the same bar, the same room where he once was.” This, of course, gives a lot of credibility to the idea that his great great grandfather actually stayed there. Or was his reply just for fun? What of the elder Dickens’ critique? Here is an excerpt:

“Take the old-established Bull’s Head with its old-established knife-boxes on its old-established sideboards, its old-established flue under its old-established four-post bedsteads in its old-established airless rooms, its old-established frouziness up-stairs and down-stairs, its old-established cookery, and its old-established principles of plunder. Count up your injuries, in its side-dishes of ailing sweetbreads in white poultices, of

The Uncommercial Traveller by Charles Dickens

apothecaries’ powders in rice for curry, of pale stewed bits of calf ineffectually relying for an adventitious interest on forcemeat balls. ”

First of all, this is Chapter VI in the book compared to the Shipwreck’s Chapter II. Nowhere in the chapter does Dickens actually mention which Bull’s Head he is referring to. Do a search of “Bull’s Head” in the UK and Google Maps will light up red. There is no link either to tie this segment to his visit to Wales. In Dickensian Inns & Taverns (1922) by a former The Dickensian Editor, B.W. Matz states:

“The innumerable references to inns and taverns in The Uncommercial Traveller are for the most part purely imaginary. Even when it is clear that Dickens is describing something he actually saw and experienced, he has taken the precaution, in this book, to disguise the inn’s name and whereabouts. There are several such in the chapter entitled “Refreshments for Travellers,” a chapter made up of a series of complaints and adverse criticisms verging on the brink of libel. ”

His first example is the excerpt I included above.

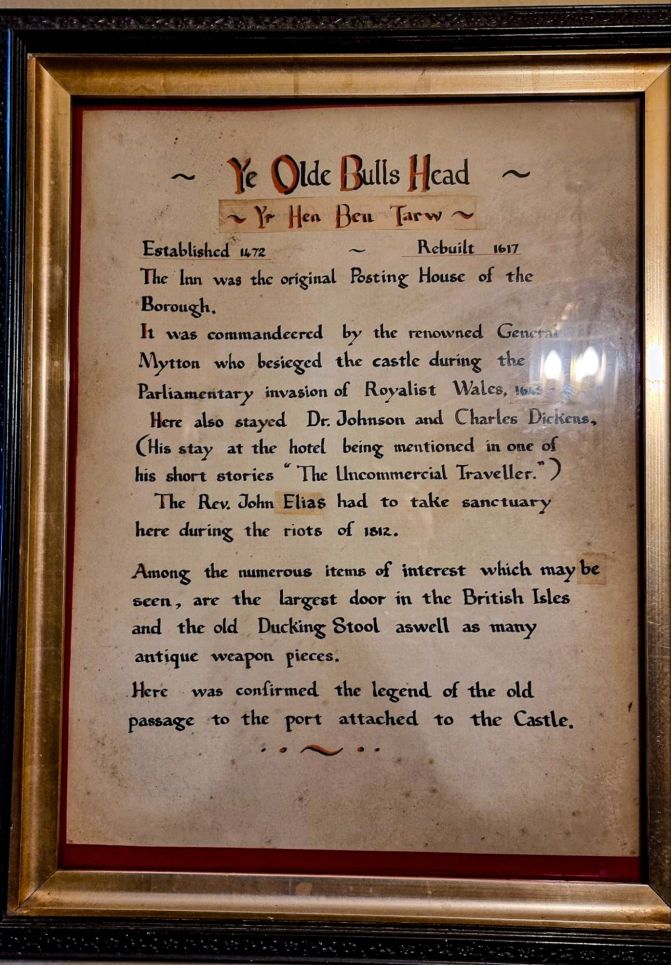

Let’s review the inevitable sign hanging on the wall.

“Here also stayed Dr. Johnson and Charles Dickens, (His stay at the hotel being mentioned in one of his short stories “The Uncommercial Traveller.”)

Dr. Samuel Johnson is often referred to in these types of signs. He was a famous English writer one century earlier than Dickens. Anywhere he stayed, inevitably so did Dickens (if you believe all the signs). But what catches my attention is the reference to The Uncommercial Traveller as one of his “short stories”. It is probably just bad wording, but as noted, The Uncommercial Traveller is a collection of articles about real subjects not stories written for his publication and assembled into a book.

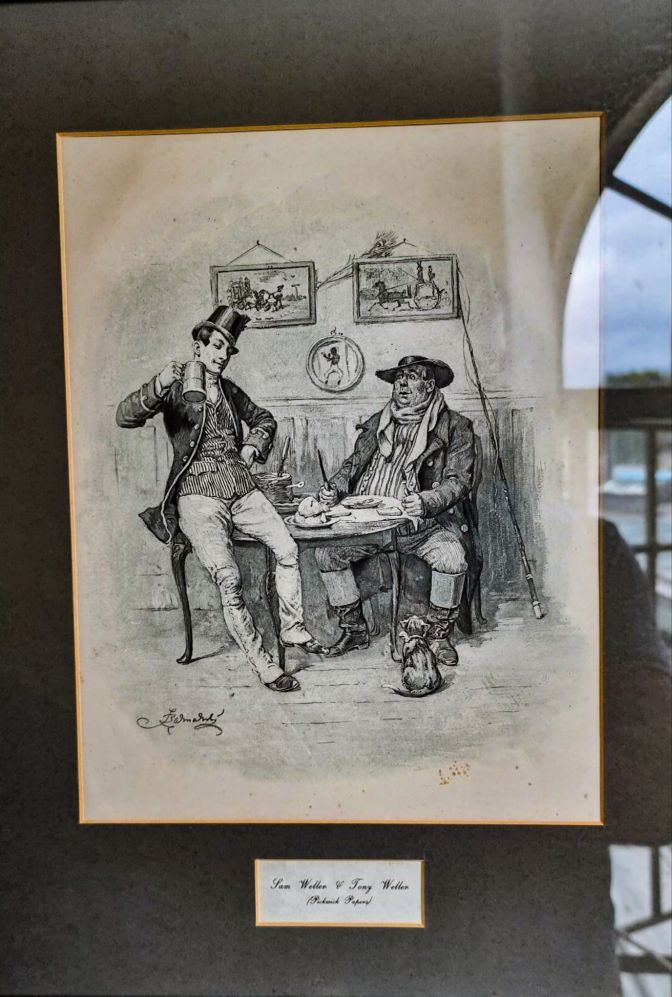

Despite the shaky link to Dickens, Ye Olde Bull’s Head is a fantastic pub with a good selection of beers on tap, several cozy rooms with a lot of exposed wood beams and all of the Victorian tavern flair that you want in a Dickensian Inn & Tavern. As an added touch, several prints of illustrations from Dickens’ books are hanging on the walls, and each room has a Dickensian name.

It seems to me that Charles Dickens’ trip to Wales in 1859, as it exists outside of his well-documented and well-travelled realm of Dickens Land and Dickens London left itself open for opportunistic landlords to put themselves on the Dickens Map. However, the scholarship that I can find about it is so atrocious that it is actually more interesting to keep these claims as part of the narrative rather than wishing them away. They don’t harm Dickens’ legacy, and they invite discussion and breathe life into a niche, harmless subject. But I still hope that at least Panton Arms will do something about their sign.

Final Remarks

“As I rode along, I thought of the many people, inhabitants of

The Uncommercial Traveller by Charles Dickens

this mother country, who would make pilgrimages to the little

churchyard in the years to come”

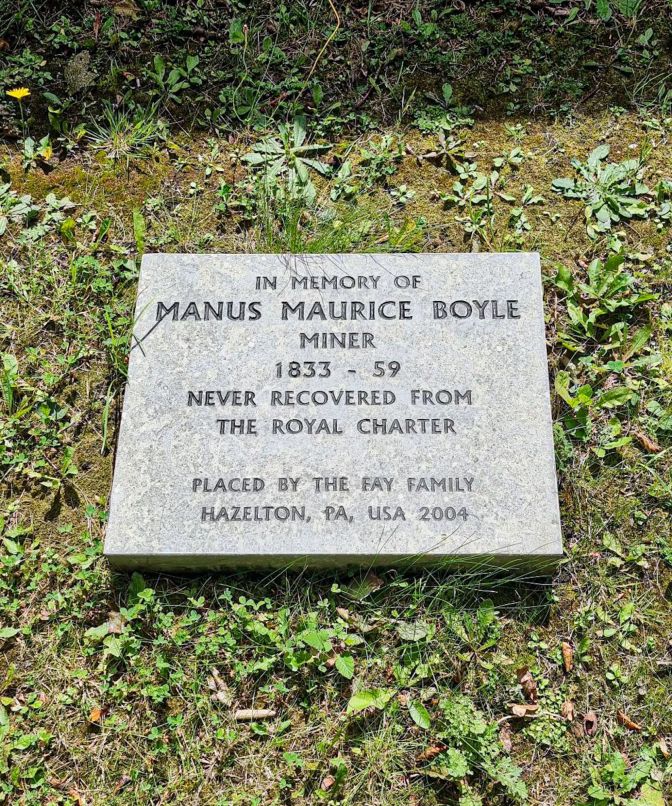

As I strolled through the old churchyard reading the headstones at St. Gallgo’s, I realized that this was going to be a moment I would probably remember as fondly as any of the hikes that I would do during my stay in Wales. The world has seen many tragedies since 1859 which have captured the sorrow, fellowship, and sympathy of human beings, and each new one pushes the old one further back in our minds. Here in this quiet, solemn churchyard was the epicenter of an event which captured a nation’s attention and tested the souls of its people. It brought its greatest author 200 miles during Winter to seek out the person most responsible for trying to bring peace to so many families. Judging from a handful of recent memorials placed in the churchyard, including one from my home state of Pennsylvania in 2004, the legacy of the shipwreck still has threads passing down from generation to generation. Yet, it is impossible not to feel the memories here fading into the maw of the modern world. In its place though are two other legacies which owe something to the Royal Charter disaster. The development of the Meteorological Office to improve weather forecasting and the awarding of a royal charter to the Royal National Lifeboat Institute in 1860 which went on to become the biggest lifeboat operation in the UK. Standing prominantly adjacent to the Royal Charter Memorial in Moelfre is a statue of Richard Evans, whose ancestors also assisted with the rescue efforts of The Royal Charter and while a member of the RNLI was responsible for saving 281 lives during his career including rescuing a shipwreck which occurred in October 1959 exactly one hundred years after The Royal Charter. That would have made an ideal follow-up article in the London Times Illustrated London News All the Year Round.

- The England of Dickens by Walter Dexter (1925) ↩︎

- https://www.peoplescollection.wales/items/44470#?xywh=-1649%2C-1%2C6692%2C4679 ↩︎

Dickens was a master of the scathing review, it seems, but left proprietors of the day without the recourse now offered by Yelp and Google. In addition to your day job and this excellent blog, btw, you could pick up work as a fact-checker if the urge arises.

LikeLiked by 1 person